The Arcades Project

This ongoing project has its starting point in Walter Benjamin’s writing and, in particular, the ‘Arcades Project’. For Benjamin the Paris arcades represented one of the fundamental early examples of the continuous interpenetration of inner and outer space. He regarded arcades and private interiors as corresponding spatial formations. It is this simultaneity of outside and inside, past and present, found elements and texts that inspired my wish to research his writing and to spend some time in Paris. For several days I walked, observed, photographed, sketched and gathered visual imagery. This allowed me to respond to a particular location (Paris), to the strange idea of an outside space on the inside (the arcades) and to assemble a collection of found and unexpected elements.

‘Homeless thoughts – a notebook is a temporary resting place for thoughts; he would have to call ‘printings’ houses. (Walter Benjamin’s Archive, p. 152)

Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project is a vast and meticulous collection of notes, images, quotes and citations, capable of being ordered and re-ordered in endlessly differing configurations. His notebooks fulfil a critical function in his practice. His writings crisscross the page with entries beginning in different parts and following diverse directions with texts interrupted and continued several pages later. Benjamin was a painstaking and obsessive ‘archivist’, always using several notebooks in parallel: the booklets for his thoughts and drafted texts, his diary, descriptions of his travels, letters, toy collection, recording every text/book he read, items he intended to read and so on. He appears to have been compulsively taking precautions with his texts, strategically placing and depositing manuscripts in the care of friends, trying to save them long before he actually had reason to do so.

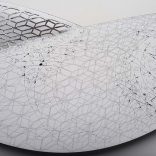

The small and smallest detail: Benjamin employed the tiniest of handwriting, almost unreadable to the naked eye, believing in the ‘aesthetic of the written sheet’ (Walter Benjamin’s Archive) and that a manuscript should show beauty as a graphic image, bringing words and groups of words into textual compositions.

Each metal panel has its ‘companion’ in paper, whether it is shown in the exhibition or not, cut in the smallest detail, echoing Benjamin’s tiniest notebooks and frenzied archiving of thoughts and collections of objects.